SUNY Plattsburgh Alumnus Leading Statewide COVID-19 Pooled Testing

Colleagues in the scientific community laughed when Dr. Frank Middleton suggested he could measure the coronavirus in saliva.

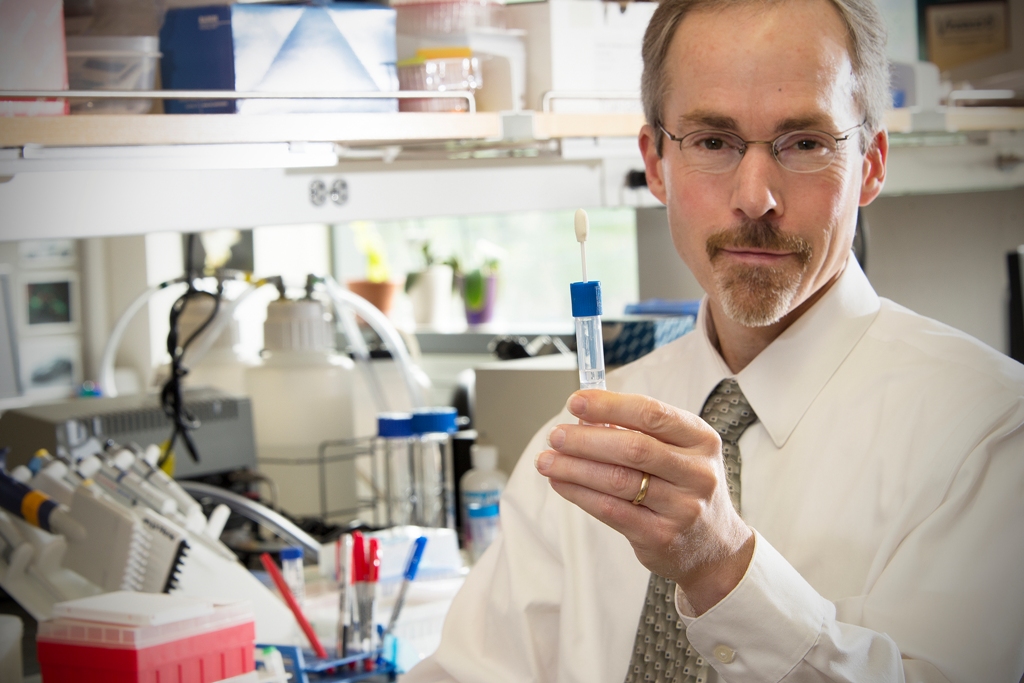

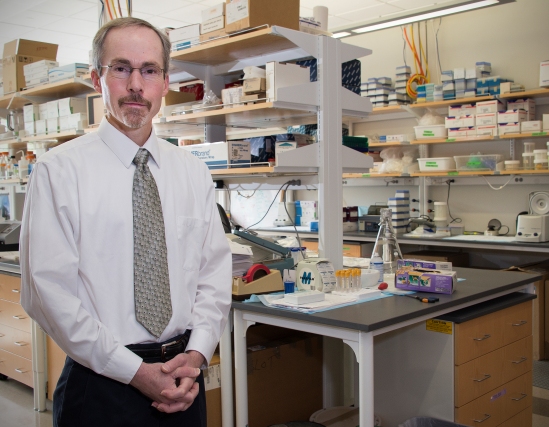

But the 1991 SUNY Plattsburgh biology grad knew it could be done. He had already developed saliva-based testing to detect Parkinson’s disease and autism based on years of research conducted in his lab at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. His saliva pool testing method, now being used to test for COVID-19 here and at colleges and universities across the state, has become an indispensable tool in fighting the pandemic.

Middleton, a Beekmantown High School grad who transferred to SUNY Plattsburgh after a year at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, said he came to the realization that saliva pool testing could be the answer to COVID testing after the Centers for Disease Control testing kits rolled out a year ago failed.

“It didn’t make sense to me that we couldn’t create a better test using saliva,” he said. He said as much to friends and fellow Upstate colleagues at a dinner party he and his wife, Michele, were attending in early March 2020.

RNA Found in Saliva

He based this on the fact that RNA — ribonucleic acid — is found in saliva and carries the genetic information found in many viruses. When the virus began to spread a year ago, Upstate, like facilities across the state and country, joined the lockdown.

But Middleton was given permission to keep working.

“I knew then that within a few months we’d be able to develop a very sensitive COVID test that would help overcome the problems we saw with testing at the time,” said Middleton, who is associate professor of neuroscience, physiology, biochemistry and molecular biology at Upstate. “The first CDC test had problems. But I had worked with saliva; I had been staying up to date with technological advances. I had expertise in the technology.”

And like those skeptical colleagues who laughed at his COVID hypothesis, Middleton faced similar doubts from the Food and Drug Administration about using saliva to test for the virus that to date has killed more than half a million people.

Permission to Stay at Work

But Upstate President Mantosh Dewan had faith in Middleton’s idea. When the virus

began to spread and the state went into lockdown, Dewan gave the researcher permission

to keep his lab open.

But Upstate President Mantosh Dewan had faith in Middleton’s idea. When the virus

began to spread and the state went into lockdown, Dewan gave the researcher permission

to keep his lab open.

Middleton brought in a dozen grad students to assist; Quadrant Biosciences, a research company at Upstate, gave him another dozen of its employees to help. A few weeks later, he had produced a prototype and saw success on saliva samples from patients in Upstate Medical.

While still awaiting word from the FDA, Middleton shared his data with the state Department of Health.

“They were very interested in our success with saliva and pooled testing,” he said. By mid-July, the state health department authorized the test to be used statewide.

On Aug. 25, SUNY Chancellor Jim Malatras announced during a visit to SUNY Plattsburgh that Middleton’s saliva swab pool testing method would become the norm across SUNY and would be used at SUNY Plattsburgh that week when students returned to campus, the first time since mid-March.

Middleton’s testing method has since been used successfully to identify the coronavirus among faculty, staff and students, including Middleton’s own son, Tyler, who’s attending Plattsburgh as a public relations major.

Middleton, whose late father, Dr. John Middleton, was a counselor and taught in human development and family relations at the college, began his path to scientific success after his year at RPI when he returned home to the North Country where he discovered Plattsburgh’s award-winning program in cell biology at Miner Institute in Chazy, N.Y.

Double Major

“The college also had an outstanding psychology program. I decided to take a few courses and became a double major in biology and psychology, creating my own path,” he said. “I realized then that I wanted to do research. I had an undeveloped minor in chemistry as well, which gave me another opportunity for research.”

It was through Dr. Jeanne Ryan, SUNY distinguished teaching professor emerita of psychology,

who encouraged Middleton to continue and earn his master’s degree from SUNY Plattsburgh,

which he did in biology in 1993.

It was through Dr. Jeanne Ryan, SUNY distinguished teaching professor emerita of psychology,

who encouraged Middleton to continue and earn his master’s degree from SUNY Plattsburgh,

which he did in biology in 1993.

“She had a biologist in her lab, and she allowed me a lot of freedom to work independently,” Middleton said.

For her part, Ryan spoke highly of Middleton, recalling how as a young man he joined the neurobehavioral science research lab when she was a new faculty member.

“He was clearly a star,” she said. “He completed his master’s under my supervision, but to tell you the truth, he was a self-motivator and needed minimal direction before he was off and running.”

She said when he was admitted to SUNY Upstate in its Ph.D. program in neuroscience, “he worked with Dr. Peter Strick, who nurtured Frank’s quick mind and talent as a scientist and guided him into the upper echelon of neuroscience research from his first publication in the prestigious journal, ‘Science.’”

Current Research ‘Not Surprising’

From there, Middleton continued his research in the motor system, “but over the years expanded his interests and investigations into challenging areas where answers were needed — like schizophrenia and autism,” Ryan said. “His current research in COVID-19 is not at all surprising. The breadth of his research is striking and a feature that I have observed only in the brightest minds.”

Having had this kind of success has been gratifying, Middleton said.

“It’s from the heart. We wanted to keep kids safe,” he said. “That was one of our motives when our (Upstate) president said to get this moving, and the chancellor said we wanted to offer this to all.”

Game-Changer in Pediatric Medicine

Dr. Alison McCrone, assistant professor and pediatrician in charge of the pediatric urgent care at Upstate, said the saliva test has been a game-changer in pediatric medicine.

“Until recently, I had to be the bad guy with many of my patients,” she said. “Virtually all of our patients these days require COVID testing; most came in and immediately asked, ‘Do I have to have the brain swab?’”

The nasal probe swabs are traumatic for most kids and frequently put the physician in the difficult position of getting close to a sick child and having them cough and sputter in front of you, she said.

With his work, Middleton has “eliminated the stress of COVID testing for so many children,” McCrone said. “He has made it safer for me to administer these tests.”

She said she wishes Middleton could see the look of relief on their faces when it’s a quick oral swab, and she gets to tell them, “Just like brushing your teeth, Buddy. All done.”

“It’s not only an improvement in comfort; I have had more kids than I can count come in to get tested because it was the oral swab and not the nasal probe one,” she said. “Their threshold for testing has reduced, thereby improving our ability to identify spread.” Her own son told McCrone he’d rather just quarantine the 14 days than get the nasal swab.

“Getting tested with the oral swab let him get back to school in a few days rather than missing weeks. That is huge,” she said.

And as one of the top researchers in the state, Middleton’s goal is the same as everyone else’s: to stay safe and keep his family safe.

“Just be smart,” he said. “Stay safe and be smart.”

News

Alumni Celebrated for Sustained Support of North Country, Residents

SUNY Adirondack Students Benefit from New Dual Agreement with SUNY Plattsburgh Queensbury